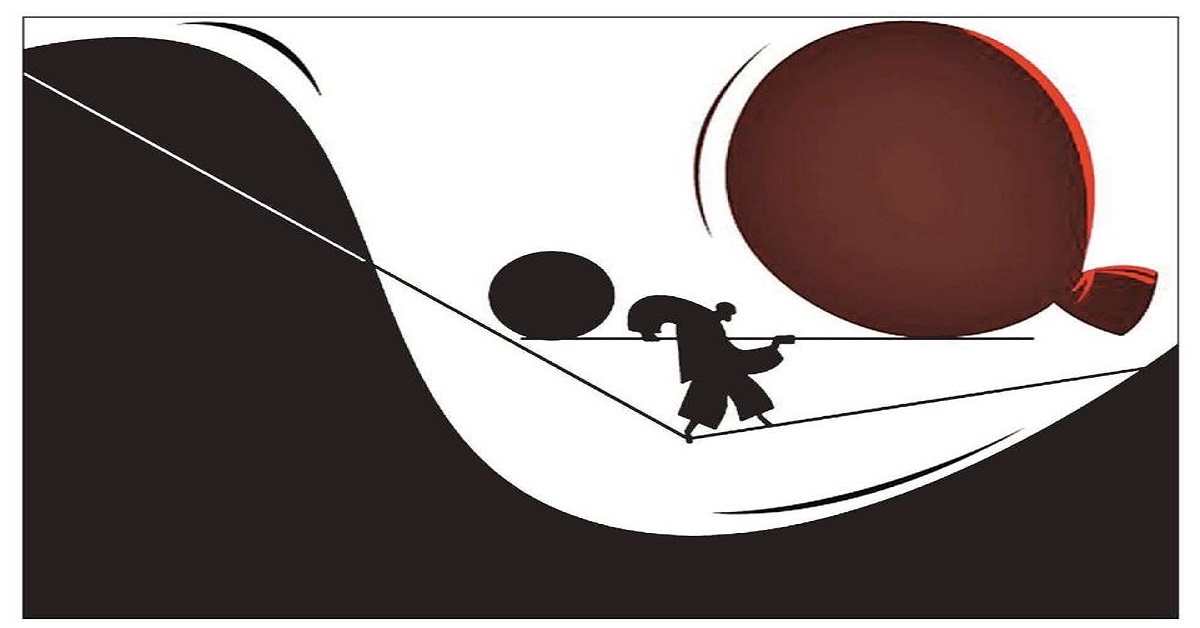

Fiscal federalism flux

The current state of confusion is rooted in several grave clefts created during the state-restructuring process

ACHYUT WAGLE

According to the Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration, only 176 local government units, including both municipalities and rural municipalities, have officially informed the ministry that they duly presented the finance bill in their respective legislatures and got them ratified. The non-compliance of ministry's repeated correspondence, latest one routed also through the District Coordination Committees (DCC), has caused serious concerns of 'federal anarchy' in the name of decision autonomy. Such recalcitrance to major 'reporting' if not the regulatory authority, for example, despite ongoing controversies like recent tax and service fee levied by the local governments, is increasingly becoming a real bottleneck to monitoring of the actual status of implementation of federalism and assess future policy calibrations. The constitution authorizes the DCC "to make coordination between the Federal and the State Government offices and Village Bodies and Municipalities in the district." So, on the part of the local levels, this may be construed as the non-adherence to the constitutional provision. In addition, aggregated data from the Municipality Association, Rural Municipality Association, and several DCCs revealed that out of 753 local governments, only 587 presented some form of budget speech in their legislatures. Out of them, 437 (including 166 yet to frame their budget or finance bill) didn't incorporate tax rate or items to be taxed as a motion for debate in the legislature before enforcing them. The quality of the budget presented also leads to next set of questions concerning the capacity on the public financial management of entire local levels; barring only a few exceptions. The federal government, that has miserably failed to depute bare minimum number of civil servants to local government units, largely appears impervious or unable to provide technical support to such causes.

Fiscal fiasco This rather hastened decision of the majority of local governments to initiate collection of taxes and fees brings three major

issues of fiscal federalism to the forefront of debate. First, the provisions of taxes, ideally, would have been made after weighing the size other sources of funds like the federal grant and the amount flowing in under the revenue sharing mechanism. Instead, the focus of the local government, for now, should have been to increase the absorption capacity of available financial resources. For almost two decades now, Nepal's most excruciating problem has not been the shortfall of resources, at least to the local level, but the inability to expend them. Mapping of demand for local development and estimation of required resources would have been the natural next step. Linking every local tax directly to public goods provided by the local government is an unequivocal public financial management norm in a federal polity which has been grossly violated. Second, regardless of whether the local entities succeed to generate substantial revenue on their own, they will relatively be cash-awash. Even the smallest possible rural municipality would get on an average, Rs100 million per year for it to mobilize from federal or state transfers. Given the absence of public procurement framework, the absence of disclosure, transparency and oversight mechanisms designed for local

government; coupled with over-enthusiasm regarding decision autonomy resulting in a spending spree by the local elected representatives are sure to make the universal cliché, 'federalism localizes corruption', self-fulfilling. The ministry says it is drafting a template of public procurement regulation meant for the local governments. But this has taken far too long. Customising these new rules in the local context, even assuming they would be received in good faith, and implementing them, pose the next level of challenge. It is particularly so given the reality that hiring of duly trained accountants, along with other general staff members, is already proving daunting for most of the far-flung jurisdictions. Third, utilizing the available funds and other factor endowments in economically efficient fashion remains 'the' problem across the country. The culture of identification and prioritization of the projects is largely imitative rather than innovative. For instance, a substantial portion of the local allocation is spent on seasonal roads which are washed away in every monsoon. Little attention is paid, instead, even to improve the quality of health or education services just because their impact is less tangible than running earth movers on the hills

. Needless to say, the availability of project planners and implementers outside of major urban centres has proven impossi-ble for decades now Without substantial structural changes both in resource alloca-tion practices and development administra-tion, of course, in line with federal spirit and aspirations, the politics of federal pow-er-sharing alone is unlikely to deliver the `goods' to the people. There are signs that new round of frustration in the masses is already in the offing.

Structural flaws The current state of federal flux is not the outcome of the inability of all three layers of the government to come into terms with the federal character of the state and oper-ational inefficiencies thereof but also root-ed in several grave clefts created during the state-restructuring and formulating the constitutional provisions. Here is a glaring one. The Local Body Restructuring Commission effectively thwarted the possibility of making each local body an economically viable unit. The expectation of the state restructuring pro-visions in the 2015 constitution was to liqui-date the district level administrative struc-ture, once and for all. Its functions would then automatically transfer to the munici-palities, the number of which was expected not to exceed 200. But the LBRC proposed very odd-sized jurisdictions as many as 720 without any scientific basis, most disheart-eningly to repeat, without any considera-tion to their (enhanced) economic viability. For example, against the constitutional provision of transferring responsibility of all high school education to local govern-ments, the district education offices are now set to continue to exist since the munic-ipalities 'proved' to be incapable of manag-ing them. The constitution not only fails to prescribe basis for local security adminis-tration, it misses defining the role of Nepal police beyond the state level. This provides an excuse for maintaining the district administration offices directly under the federal ministry of home affairs. The government's failure to constitute the National Natural Resources and Fiscal Commission and formulate regulations related to three key laws; NNRCF Act 2017, Intergovernmental Fiscal Transfer Act, 2017 and Local Government Operations Act 2017, has contributed to the uncertainty. The NNRFC, even if constituted, has been made so toothless that without expanding its mandate as a quasi-judicial constitution-al body according to the best global practic-es, it cannot contribute to institutionalising the federal polity